Switching to Vim

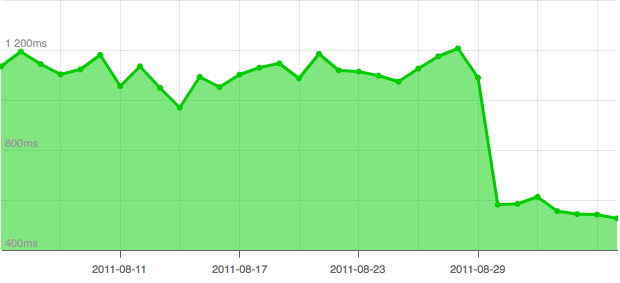

A few months ago, I stopped using TextMate as my primary code editor in favour of Vim (specifically, MacVim).

I first encountered Vim as a Linux-curious high-schooler, and had been averse to it ever since.

The requirement to press i before inserting text seemed ludicrous to me.

To navigate with hjkl instead of the arrow keys was like a masochistic exercise in self-deprivation.

Like most of my generation, I learned the Microsoft Word/Notepad style of text editing, which is totally incompatible with how one uses Vim.

On the rare occasion that I felt brave enough to use Vim, I’d make lots of mistakes, and I’d usually give up and use nano instead.

But in 2011, there was a tide of positivity about Vim, and I couldn’t ignore it. It was Vim’s 20th birthday, and there were lots of articles online about how productive it made its users and how rewarding it was to learn. My friends George and Nick would tweet about how they’d tweak their Vim setups for maximum efficacy, and my geek pride was dented somewhat by my inability to take part in their discussion. I watched people code in Vim, and not only had they overcome the learning curve, they were moving with incredible speed. The biggest factor for me, though, was that TextMate seemed to be stuck in a rut. There hadn’t been any major changes or improvements to it, and there was no indication of when TextMate 2 would come out (of course, TextMate 2 Alpha was released in December, but by then I had already switched to Vim). The time seemed right to give Vim another chance.

The switch

As expected, my first couple days in Vim were not hugely successful.

It’s difficult to unlearn years of editing text the “usual” way.

The most important insight I’ve had since I switched is that I spend most of my time as a coder editing code, not inserting code.

Viewed in this light, Vim’s distinction between insert mode and normal mode makes lots of sense.

Vim’s major advantage over other editors is the speed with which I can move around and manipulate code, even if I’m no faster at inserting new code.

If you’re starting out, I’d recommend you get comfortable with b, e, and w first, as well as the hjkl home keys.

Once you’re moving around without having to think about your keypresses, start referring to the cheatsheets at the bottom of this page.

You’ll be a Vim guru in no time!

Resources

If you’re curious about Vim, there is a wealth of resources that’ll get you started. I use Janus, a distribution of common plugins that provide many of the comforts of TextMate. Not everybody thinks Janus is a good idea, but I like it and am sticking with it for now. It’s worth printing out a couple cheatsheets: this one and this one are my favourites. This post about Vim Text Objects is a goldmine of information. One of the most inspirational articles I read was Staying the hell out of insert mode, which really emphasized for me how great normal mode is and has done a lot to inform my overall philosophy on Vim.

If you’re curious to see how my Vim is setup, my personal dotfiles can be found on my GitHub.

In conclusion

I think switching to Vim is one of the best development decisions I’ve made recently. It enables me to work much faster than I could previously, and I’m proud that I can edit files in the terminal without resorting to lesser editors. If you’re curious about Vim, I’d strongly recommend trying it out. It’s definitely a little painful at first, but you’ll be surprised at how much more effective you become.